Their seems to be a debate over whether or not to leave the catheter in place or remove it after performing a Needle Thoracentesis (needle decompression). The Committee on Tactical combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC) doesn't discuss this in their recommendations, they only specify decompression landmarks. Typically the units Senior Medical Officer determines the protocols and will set the policy on the procedure. Having taught TCCC / TECC to thousands of students over the past ten years or so and I would estimate that most medics remove the catheter upon relief of symptoms. Does that mean leaving the catheter in place is wrong? No it does not, often in tactical medicine it's not about right or wrong, it's about "what's the most appropriate thing to do right now, based on the current situation".

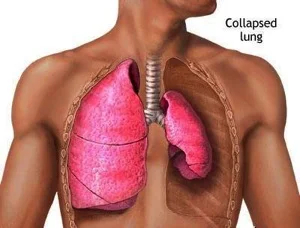

Before we discuss the pros and cons of both options, lets be clear on what's is most important. A Tension Pneumothorax is a life threatening condition that requires immediate relief any discussion over the disposition of the catheter is really spitting hairs. Tension Pneumothorax continues to be the #2 cause of preventable death in combat trauma, despite the military wide acceptance of TCCC /TECC and the fact that all medics and many non-medics are provided a 14 gauge needle as well as authorization to decompress. Needle Thoracentesis is a life saving intervention but it's not typically considered a treatment, it is considered to be a diagnostic tool and a stop-gap intervention as it does not treat the underlying injury.

LEAVING THE CATHETER IN PLACE

PROS

- Easy to identify that the patient may have had a Tension Pneumothorax and that a decompression was performed and may alert new providers to be on the lookout for return of symptoms.

- Easy to identify which side has been decompression was attempted on.

- Easy to determine how many times a decompression has been attempted based on the number of catheters left in place.

CONS

- Believing that it will continue to work and allow air to escape, it typically kinks and clogs and doesn't prevent the need for subsequent decompressions. If providers make this assumption they could potentially miss the return of symptoms.

- Increased risk of infection.

- If removed carefully it could potentially be used multiple times, keeping in mind that non-medics typically don't carry multiple needles. Using your only catheter once would require a non-medic to have to do subsequent decompressions with only a needle, thus increasing patient risk.

MONKEY OPINION SECTION:

Committees, agencies, states, rules and regulations aside here my personal opinion on the disposition of the catheter:

I remove it after I see relief of symptoms, typically after about 45 seconds and a few good breathes coupled with some manual pressure on the patients chest. That is the way I was originally taught how to do it and that's what I have stuck with, however I see nothing wrong with leaving it in place if that's what you so choose. Truthfully the disposition of the catheter is of very little consequence to me, what I'm much more concerned about is recognition of the symptoms and the life saving intervention. Tension Pneumothorax is the second leading cause of preventable combat death.1 Almost everyone is trained and provided a 14 gauge needle and we still have folks dying from a preventable injury. Why?

Why does this continue to kill patients?

Here is why I believe it continues to occur and how to solve the issue:

During training it's a simple catch, especially after a 45 minute Powerpoint on Respirations or when standing over a mannequin with latex cutouts inserted over the landmarks. Amped up, in real world emergency with a multi system trauma victim it's not always so obvious. I will put a list of the twenty or so signs & symptoms down below and I'm sure most of our readers are familiar with them, however some of them are not as common as we have been led to believe. A Tension Pneomothrax is a progressive respiratory disease. Patients are not going to initially present with a dozen symptoms, they will typically have one or two and if untreated, those symptoms will progress and it's likely more symptoms will present. Evidence suggests that patients have progressive respiratory deterioration with final respiratory arrest. The key to interpreting the early signs of hypoxia and respiratory distress is the degree of severity, but more importantly a pattern of relentless progression in a patient at risk of tension pneumothorax.4

Another important distinction to point out here is that most military medics are not carrying O2, administering O2 will have a profound impact on cyanosis, SpO2, and neurological function. Oxygen obviously benefits the patient but it does not treat the underlying problem and can mask symptoms.

- Problem -

- Not recognizing the patient has developed a Tension Pneumothorax.

- Not willing to insert a 3.25" needle into a patients chest.

- Solution -

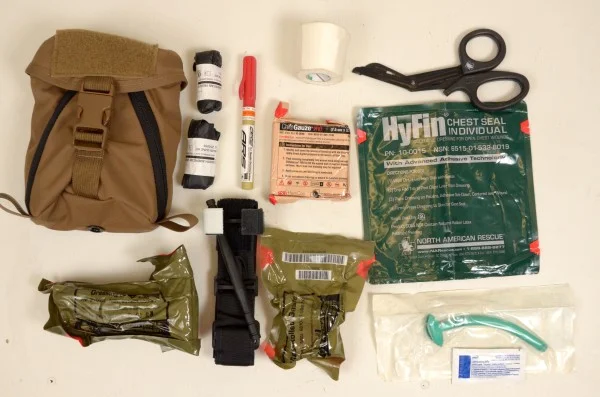

Train everyone, medics included to treat patients based on what is in an Individual First Aid Kit (IFAK), not what is in a robust medical bag. A standard IFAK should have a Tourniquet, a Nasopharyngeal airway, gauze, pressure dressing, chest seals, and a 14 gauge needle. If you are treating a patient and he/she is in progressive respiratory distress, look in your IFAK and see what hasn't been utilized. If there is still a needle in the kit, then that should be your clue. If you haven't utilized your chest seals, then that should be the prompt to double-check for any holes that need to be sealed up, remembering to seal all holes regardless of size from the navel to the neck 360 degrees. A Tension Pneumothorax is an absolute life threatening conditions and if you have tried all other treatment options (recheck for holes, re-position), then it's probably time to dart.

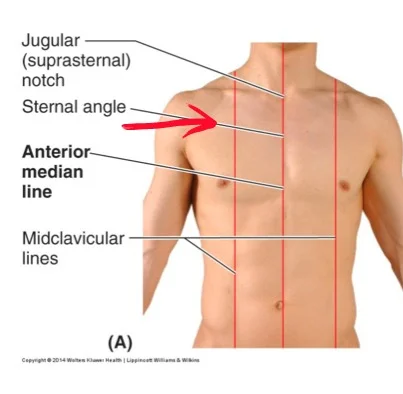

To overcome the issue of not wanting to go Pulp Fiction and stick someone with an excalibur sized needle through the proverbial breastplate we need to continue to stress in training that an Needle Decompression is safe when performed correctly. Teach the right technique and the right location and emphasize the minimal risks associated with the procedure.

Not wanting to make the patient worse is the typical response given when poor or no medicine is performed. A needle decompression is one of the few procedures you can perform that will often result in an immediate improvement of symptoms.

Signs & Symptoms

Courtesy of Reference 4

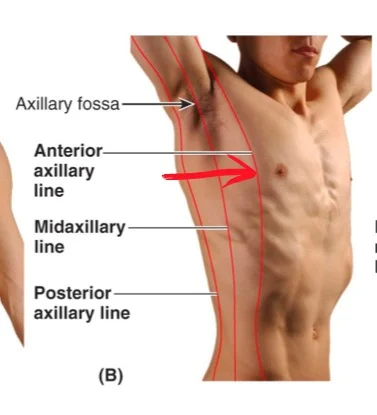

LANDMARKS

2nd Intercostal space mid-clavicular

5th Intercostal Space Anterior Axillary

SURVEY

Trauma monkey tips:

- Chest examination, chest seals, and needle decompression are all performed in Tactical Field Care (TCCC) or Warm Zone / Indirect Care (TECC) never in Care Under Fire or Hot Zone.

- Thoroughly examine the armpit area / axilla, it's not protected by body armor and holes are commonly missed in that region.

- Utilize an interlaced hands raking technique to try to find holes, it's not always obvious.

COVER ALL HOLES - Chest Seals can never save a life if they are left in the IFAK.

- CoTCC is now recommending using a vented chest seal there is not much literature to support the effectiveness of the vent, I wouldn't toss my non-vented seals just yet.

- Applying a vented chest seal does not guarantee a patent one way valve will effectively prevent a tension pneumothorax from occurring be prepared to burp or decompress.

- When applying a chest seal use a band-aid technique, peel only a small portion of the back, affix it to the area, and pull the backing away. Newer style seals are extremely sticky, if you peel the entire back off they will likely stick to your hand, gloves, anything else that it comes in contact with it.

- Chest Seals can be cut to create multiple seals, this is important to those carrying IFAKS with only one seal.

- If you only have one seal, use it on the biggest baddest hole. Covering a small entrance wound on the front side with your one good seal is a bad idea as there may be a large exit wound on the down side.

- Aggressively wipe off the area prior to placing the seal. Most seals come with a small amount of gauze but it's rarely enough for a bloody hole on a sweaty man-bear-pig, I use my sleeved arm to scrub the area.

- After you seal the holes, if the patients demonstrates any signs of respiratory distress, go back and re-assess your seals and verify that you haven't missed other potential holes use the DART technique.

- If the mechanism of injury is a gun shot wound or blast injury there is no such thing as a superficial chest wound. Assume that all holes are devastating and cover them, a chest seal never saves a life if it remains in the IFAk or med bag.

- Needle Decompression is not the only way to relieve a tension pneumothorax, remember that simply lifting the seal and "burping" the wound may relieve the trapped air. This is especially true with larger holes that were actively sucking air in prior to chest seal placement.

- Needle decompression and Burping will do nothing to alleviate a Hemothorax. Remember that each side of the chest can hold up to 1500ml of blood and pre-hospital chest tube placement is not a routine procedure for most. Repositioning the patient can and will move the blood and potentially improve symptoms.

- Textbooks say to place the injured side of the chest down, I have yet to met a chest that reads textbooks. A conscious patient will position him/herself in the position they are most comfortable, DON"T force them to lie down. Unconscious patients should be placed in the position that they seem to breathe best in, if unattended the must be in the Recovery position.

- Blast lung and blunt force trauma victims may not have obvious injuries, remember the MOI.

- Non-medics will not have the benefit of a stethoscope so diminished breathe sounds will be difficult if not impossible to ascertain. They are going to have to determine which side needs to be decompressed relying on outside injury pattern and potentially from unilateral rise & fall.

- People come in all different shapes and sizes, a 3.25" needle is to help get through the large muscled,barrel chested, meat eater, it would likely pin a small person to the ground. The needle is designed to get the catheter into the pleural space, the catheter is then advanced. Advance the needle until you feel a pronounced pop and lack of resistance, then slide the catheter forward minimize the depth of needle insertion if at all possible.

- Listen for a whoosh of air, this is actually a diagnostic finding to confirm a tension pneumothorax, keep in mind that it can be difficult to hear in an real world environment. More important then the whoosh of air is patient improvement.

- If you do not have a catheter you can perform the procedure with just the needle portion, only penetrate as deep as is needed and NEVER leave the needle in place.

- Note the time of the decompression as it is only a temporary fix and likely to recur. Tracking the time allows us to predict these recurrences.

- Remember to remove the protective tab or luer lock port that's above the flash chamber as it may prevent air from escaping. Needles made specifically for decompression like one pictured at the top of the article do not have this cap.

- Catheter may be advanced too far and its distal opening may be in contact with lung tissue preventing it from evacuating air, backing it out slowly may seat it in the air pocket and facilitate decompression.

- Needle Thoracentesis will not remove all air from the pleural space, it will vent air until pressure in the space is equal to atmospheric pressure outside the chest. The patients lung will not instantly re-inflate, this will require a chest tube and time.

REFERENCES:

Prevalence of Tension Pneumothorax in Fatally Wounded Combat Casualties John J. McPherson, MS, David S. Feigin, MD, and Ronald F. Bellamy, MD, FACS (2006)

Needle Thoracostomy by Non-Medical Law Enforcement Personnel: Preliminary Data on Knowledge Retention

Matthew D. Sztajnkrycer, MD, PhD (2008)

Death on the battlefield (2001Y2011): Implications for the future of combat casualty care

Brian J. Eastridge, MD, Robert L. Mabry, MD, Peter Seguin, MD, Joyce Cantrell, MD, Terrill Tops, MD,Paul Uribe, MD, Olga Mallett, Tamara Zubko, Lynne Oetjen-Gerdes, Todd E. Rasmussen, MD,Frank K. Butler, MD, Russell S. Kotwal, MD, John B. Holcomb, MD, Charles Wade, PhD,Howard Champion, MD, Mimi Lawnick, Leon Moores, MD, and Lorne H. Blackbourne, MD

Tension pneumothorax—time for a re-think? S Leigh-Smith1, T Harris2 (2005)

Clinical manifestations of tension pneumothorax: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis Derek J Roberts12*, Simon Leigh-Smith3, Peter D Faris24, Chad G Ball156, Helen Lee Robertson7, Christopher Blackmore1, Elijah Dixon12, Andrew W Kirkpatrick168, John B Kortbeek168 and Henry Thomas Stelfox289 (2014)